New Page

New Page

Field Marshal Douglas Haig

Hero or Villain?

A controversial figure who played a huge part in the Battle of Passchendaele

the actions of the accused

Field Marshal Haig was in command of the British Army during the Battle of the Somme, the Battle of Passchendaele, and the following Hundred Days offensive. Over 2 million British soldiers died under his command in these battles, yet without an Allied victory it is unlikely that the British would have "won" the First World War.

The actions of Field Marshall Haig are considered by some evil, and others heroic. Many today refer to Field Marshall Haig as "Butcher Haig," for his costly tactics, yet others believe he was a great leader of the British Army.

As Haig appears in front of the Court today, it is up to you, the judge, to decide his fate. Should he be sent to the firing squad and remembered as a villain, or celebrated and be thought of as a hero?

New Page

New Page

Butcher Haig

Your Honour, today I will comprehensively prove that the actions of Field Marshal Haig were morally bankrupt, lacking any intelligent strategy, and were certainly not the best course of action to take at any of the battles he participated in. Haig should not be hailed as a hero, rather he deserves what he sent so many of our men out into; bullets.

The somme

The strategy that Haig employed at the Somme was a terrible one. After a week of constant artillery fire onto the German trenches, Haig was so confident of his victory that he ordered his troops to walk into no mans land, ready to mop up any wounded German soldiers. The Germans, seeing the artillery shells entering British lines, had set up fortifications that stopped the artillery from being effective. When the British marched in neat lines towards them after the barrage, the Germans wound up their machine guns and massacred thousands of Allied soldiers, including many Kiwi's.

Is this an acceptable military strategy? Should this man be celebrated for sending thousands over the top to be slaughtered due to his mistakes? War crimes have been committed which have seen less victims killed. Can we accept the death of 420,000 British and Kiwi troops as a "Victory?"

passchendaele

The heavy rain, terrible wind, and all covering mud made the site of the Battle of Passchendaele one of the least forgiving of the First World War. Haig's failed tactic of artillery bombardment was attempted again here, yet the mud provided no support for any of these machines. Regardless, Haig was all to eager to send his men back over the top, this time with no artillery support, into German fire.

Clearly, the weather was appalling, no tank or artillery support was available, and the battlefield was little more than a bog. Why then did Haig not postpone the Battle of Passchendaele? The lion cubs, young New Zealanders with little experience, were made to walk into no mans land like lambs to the slaughter. How can we justify this strategy? Is it morally acceptable to carry out a battle plan despite everything going awry, see it fail horrifically, then praise the man who planned it?

Legacy

Your Honour, it is as clear as day to me that the actions of Field Marshall Haig throughout the First World War were truly terrible. He sat behind the lines, ordering young New Zealand husbands and fathers out to their deaths. The machine guns lay waiting at the Somme and Passchendaele, yet despite Haig's "Brilliance" he continued to provide them with targets, well past the point it where it could be justified.

Books have been written praising the actions of this man. His funeral was a day of national mourning in Britain. Yet how many of those widows and children mourning his death would realise that Field Marshal Haig was the sole reason for the death of their husbands and fathers? In the name of those who suffered at Haig's hands, this man presented before you deserves the same fate that he delivered to millions of British and New Zealand troops. Bring in the firing squad, and end the life of the man who has ended the life of 2 million grandfathers, brothers, husbands, and fathers.

New Page

New Page

Master of the Field

Your Honour, Sir Douglas Haig was truly a "Master of the Field," and was directly responsible for capturing Entente objectives at Passchendaele and the Somme. Without his leadership, support and strategy, the German forces would have completely demolished any Entente push, attack, or chance of winning the First World War. His contribution to the war effort was so great, and so crucial, that this man should forever be remembered as an inspirational wartime leader.

Haig inspecting his forces

In the field

Field Marshall Haig was a truly inspirational leader, and his impact on the morale of the troops cannot be understated. Always surveying, Haig would never be caught off guard, and did his utmost to ensure the safety of his men on and off the battlefield.

On the Battlefield

strategy

Haig's strategies are regarded by many as the reason why Britain was victorious in the war. Never straying from his plans, Haig doggedly pursued his objectives, be they distracting the German troops, capturing key locations, or attacking German supply lines. Everything that Haig did, he did to ensure Britain would win the war, with no cost too great to secure the safety and happiness of the British people.

A coloured image of Haig

LEgacy

After the end of the War, Sir Douglas Haig was treated as a war hero. Yet even this newfound admiration did not stop Haig doing his best for the British people. Haig spent the rest of his days fighting for the rights of returned soldiers, reinforcing the respect he had gained during the war. He will forever be remembered for his devotion to duty, his intelligent strategy, and most importantly for achieving key objectives in a number of battles, such as Passchendaele and the Somme, which led to Britain being victorious at the war's conculsion.

New Page

New Page

Is Field Marshall Haig Guilty or Innocent?

New Page

New Page

The Verdict

Field Marshall Haig has been shown by the prosecution to be a monster, yet a true British hero has been presented by the defense. Does the British victory at the war's conclusion justify the millions dead? Or should Haig be forever remembered as the "Butcher" that the enormous, tragic death toll paints him to be.

Should Haig be sent to the firing squad? You decide. Consider the stories of Edith, Hugh, Thomas, Otto and Hemi before you vote, and do not be too quick to sentence another innocent man to death.

Write to us with your verdict. Vote in our interactive poll. See what others think on the graph below.

Gallipoli vs. Passchendaele

Our Darkest Days

Gallipoli vs. Passchendaele

Our Darkest Days

Gallipoli vs. Passchendaele

At Gallipoli, New Zealand saw her first innings in the horror and futility of modern war. Even the veterans of the infantry and rough riders of the Boer War weren’t prepared for utter loss of life that awaited at Gallipoli. Two years later, at the Battle of Passchendaele, what transpired turned out to be New Zealand’s worst military disaster yet. However, it is often overshadowed by New Zealand’s first engagement in the First World War and less people know about this massive event than those that know of Gallipoli.

The lesser of two evils?

While Gallipoli is remembered by most New Zealanders as the tragedy that shaped our national identity, how does it compare to the Battle of Passchendaele?

Gallipoli

At Gallipoli, around 2779 Kiwis died, one sixth of the estimated 17,000-18,000 strong New Zealand force that landed there. At Gallipoli, New Zealanders fought under their own flag for the British Empire for the first time since the nation’s inception. Gallipoli was a totally fruitless campaign that saw many brave young men die for nothing. Every man there was a volunteer, they had no idea what they were in for which is part of why Gallipoli is remembered as such a shocking event.

Passchendaele

All of this horror and devastation however, was nothing compared to the slaughter at Passchendaele. Gallipoli was a disaster but Passchendaele was a tragedy, with 4879 casualties by the end of it all. With 846 Kiwis dead on a single day, the 12th of October, New Zealand’s blackest day. Many more died of wounds received on that day over the coming days. The failure of the campaign was in only having advanced some 8 kilometres whilst losing over 245,000 British soldiers in a mere 100 days. To make matters worse, they were forced to abandon every metre of that blood soaked ground in March 1918 during the German Spring Offensive.

Maori and The Great War

Their War?

Maori and The Great War

Their War?

Above: Māori Soldiers in Wellington. Second from the left is Rikihana Carkeek who kept a diary about his experiences in the Great War, find out more about his story on NZ History’s page here: https://nzhistory.govt.nz/media/video/rikihana-carkeek-great-war-story?fbclid=IwAR26ul0uGOu6wt8Pdd-sJdDdleznNyHVMr8xEvUuf3hTdIj3lvrezPodAA0

Māori and the Great War:

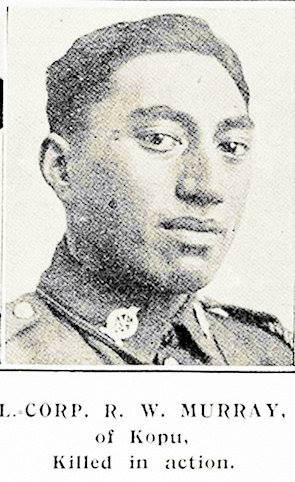

New Zealand was a very young nation at the start of the Great War, having only experienced one other overseas conflict prior; the Second Boer War. Prior to this, New Zealand itself was a battleground in the years following the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi in 1840. The Waikato Wars and the War in the North, were still in recent and even living memory when New Zealand was thrust into mankind’s greatest conflict at the time. Having only recently fought against the British, some Māori were more than a little apprehensive about fighting in a war for Britain. However, others, were prepared to serve and more than 2,000 Māori soldiers did. Initially, the Imperial authorities were wary of using, ‘natives,’ in a war alongside Europeans, yet the Māori soldiers proved their value as effective shock troops and satisfied a need for more men in a war of attrition. Māori soldiers were all volunteers despite efforts to conscript more. They were recruited through the Native Contingent Committee, involved in this effort were outspoken proponents of Māori involvement Māui Pōmare and Apirana Ngata – both Māori members of Parliament. The majority of Māori served in the Pioneer Battalions which were used as labour units close to the front line. Pioneer battalions were responsible for constructing roads and trenches, installing barbed wire and filling craters. They also established the telephone wires vital to battlefield communication.

‘The spirit of his fathers', by William Blomfield, a propaganda poster depicting a Maori soldier fighting the Turks in 1915 with a ghostly Māori warrior behind him. An effort to evoke the warrior spirit and encourage more Māori to join the war effort.

Why did some Māori fight for Britain?

Māori had as many reasons to fight in the Great War as they did to stay out of it, yet tribal divisions and colonial history played a significant role. For those Māori that did go away to fight, the promise of adventure, respect or mana and propaganda were reasons for Māori soldiers to enlist just the same as NZ Europeans. Furthermore, just as some NZ Europeans were shamed into fighting, the courage of those Māori not contributing to the war effort was called into question. Most notably by ‘Te Ope Tuatahi,’ Āpirana Ngata’s waita aimed at boosting Māori recruitment (see below). For NZ Europeans, most identified as being British and wanted to serve their King and Country in the war. Māori also had other reasons, they may have fought less out of a sense of duty and more out of a desire for fair and equal treatment in colonial New Zealand.

The lyrics and an English translation of them can be found here: https://nzetc.victoria.ac.nz/tm/scholarly/tei-CowMaor-t1-back-d1-d3.html

You can find other Māori World War 1 songs here: https://www.folksong.org.nz/te_ope_tuatahi/index.html

Sir Āpirana Turupa Ngata

Appears on the New Zealand $50 note.

However, not all Māori wanted to fight, some didn’t want to join those who were their enemies only a few generations ago in a war far from home.

‘We have our own King.’

Princess Te Puea Hērangi

Waikato Maori Resist Conscription - WW1

Forced to Stand in Line?

Waikato Maori Resist Conscription - WW1

Forced to Stand in Line?

Resistance to Conscription by Waikato Māori:

The Battle of Rangiriri, a pivotal battle for the Kingitanga during the Waikato wars.

Wounds still raw:

With World War 1 taking so many lives, the government needed more men for the war effort. Thus, they passed a law that would force those men called up to join the army and fight in the Great War. The Conscription Act of 1916 saw many New Zealanders who had not already volunteered pressed into service in the Great War. This particular issue was divisive among NZ Europeans but even more so among Māori. There were many Maori who supported it, some had even volunteered beforehand – such as Peter Buck, a Māori MP – whilst others resisted the new law. This resistance was unsurprisingly concentrated in the Waikato region. The Waikato had been the site of conflict between the New Zealand based colonial authorities and the Kingitanga movement. A Māori kingdom the size of Belgium, which in 1863 fought a war with British colonial authorities which ended with harsh consequences for the defeated Kingitanga. Much of their land was confiscated, leaving those Māori poor and bitter about the relatively recent conflict. Not to mention a number of other incidents in which the Māori were harshly dealt with by colonial authorities for even non-violent resistance, as occurred at Parihaka.

This was all still in living memory by the time of the Great War and when the conscription act was extended in 1917 to cover Maori, primarily done to tap into the wealth of manpower available from Waikato iwi, it reignited these historical tensions. With the rallying cry, 'We have our own King,' many Waikato Māori fought conscription.

The conscription resistance movement:

Foremost among them was the leader of the Kingitanga movement, Te Puea Hērangi, the grand-daughter of the second Māori King, Tāwhiao, who had led the Kingitanga in the war of 1863 and 1864. Te Puea was determined to uphold what her grandfather had declared upon making peace with the NZ Colonial government in 1881, he called for the Waikato to 'lie down,' and not allow, ‘blood to flow from this time on.' Te Puea kept this promise and organised the men who had defaulted from conscription along with their supporting iwi to meet at Te Paina near Mangatāwhiri. A deliberately small group of police officers were sent to go to this meeting and apprehend those called up. Once they arrived they were formally greeted and the leader of the officers asked for the men called up to step forward. Te Puea responded with her now famous words, "These people are mine … I will not agree to my children going to shed blood. Though your words be strong, you will not move me to help you. The young men who have been balloted will not go …You can fight your own fight until the end."

Te Uruwera and the Tūhoe

While Te Puea rallied Waikato Maori against conscription, the Tūhoe iwi of the Uruwera ranges also resisted conscription. They were led by Rua Kēnana at the Tūhoe settlement of Maungapōhatu. In 1915, Kēnana was charged with illegally selling alcohol which provided the government with an opportunity to put a stop to him dissuading Maori from enlisting. In 1916, the regional Police Commissioner John Cullen went to the Uruweras to arrest Rua Kēnana. The incident was not a peaceful one and violence ensued once Kēnana and his son were arrested. It is unknown who fired the first shot, but the resulting gun fight led to the deaths of Kēnana’s son Toko and his friend Te Maipi. Rua Kēnana was thereafter sentenced to labour and imprisonment though he was released in 1918. The result of this confrontation was the decline of the Maungapōhatu settlement and bitter memories which remain among Tūhoe members today. Combined with the fact that the Tūhoe iwi did not sign the Treaty, this event and others since have contributed to a distinctive Tūhoe identity. This is reflected in the iwi taking over management of the Uruwera ranges and the people there, who live in isolated communities, referring to it as ‘the Tūhoe nation.’ In 2019, the Crown officially pardoned Rua Kēnana by Act of Parliament and apologised for his arrest. You can read the pardon here: (https://www.legislation.govt.nz/act/public/2019/0084/latest/whole.html?search=ts_act%40bill%40regulation%40deemedreg_rua+kenana_resel_25_a&p=1#LMS215394).

King Tāwhiao, Te Puea’s Grandfather and the Second Māori King.

A popular song about Rua Kēnana, notably, the lyric ‘told his people not to go to war, let the white man fight the white man’s war,’ alludes to Kēnana’s anti-conscription stance. This video also shows more recent expressions of Tūhoe identity as well as mentioning the name ‘children of the mist’ which is attributed to the iwi.

…You can fight your own fight until the end."

Te Puea Hērangi

Peace endured:

The potential for violence to break out was high, yet never realised. Many of those called up remained with Te Puea whilst a good number were sent off to be trained at the Narrow Neck Camp, of the 74 conscripts sent to the Neck, none were sent overseas. A total number of 552 Māori were called up, some were arrested in 1919, but all were released. This meant that only those Māori who volunteered fought in the Great War.

While the service of all New Zealanders in Belgium is commemorated there at the New Zealand Memorial and Garden and many other sites, the service of Maori soldiers has been highlighted with the erection of a Pou Maumahara. The Pou was carved by the New Zealand Māori Arts and Crafts Institute at Te Puia in Rotorua. You can find out more about it on Te Puia’s website (https://www.tepuia.com/nzmaci/the-national-wood-carving-school/pou-maumahara/), our website (https://passchendaelesociety.org/pou-maumahara/) by watching the following video and reading the linked article:

For an incredibly detailed account of the experience of Māori and Pacific Islander soldiers during the Great War, check out this excellent book.

Whitiki! Whiti! Whiti! E!: Maori In the First World War by Monty Soutar

Article: https://www.teaomaori.news/te-puia-master-carver-hangs-tools-after-55-years

https://www.rnz.co.nz/news/national/387328/anzac-pou-maumahara-on-belgian-battleground-honours-nzers

New Page

New Page

The Consequences of Passchendaele

The funeral of Henry James Nicholas VC, a New Zealand soldier who won the Victoria Cross at Polderhoek Chateau on the 3rd of December of 1917. Nicholas died on the 23rd of October 1918 near the River Ecaillon in France. He was buried at the Vertigneul Churchyard with full military honours.

With the massive loss of life at Passchendaele in Belgium, things got considerably harder back home in New Zealand. While the men had gone to fight for Belgium’s freedom, they left behind children, wives, mothers and fathers. The impact did not stop there, extended family and community groups such as churches or committees left devastated. Jobs needed filling as men with experience had fallen in battle. The loss of so many young men meant that everyone knew someone who had died, leaving small towns and villages across New Zealand in mourning. In effect, a whole generation had disappeared, those who had returned were not the same, scarred forever by the war. New Zealand grieved for her lost youth.

New Page

New Page

The Lost Generation

Of the 100,000 that left for the war, 20,000 Kiwi Soldiers never returned. The impact this had on New Zealand was enormous, with everybody in New Zealand finding themselves directly affected, be it from the death of a family member or friend.

Brothers and sisters, mothers and fathers.

As 4,633 New Zealands lay buried in the muddy fields of Belgium, New Zealand was left to comprehend the vast loss of life numbering as many as 18,277 in total for the Great War. Those who did return were never the same, many shell shocked soldiers constantly reliving the horrors of the trenches, and never readjusting to civilian life. The communities that were once bustling, such as Edith's Masterton and Hugh's quiet Dunedin suburb, now resembled ghost towns. Yet life had to go on, and the painful process of rebuilding began in 1918, the Brothers, Sisters, Mothers and Fathers who had made New Zealand what it was lost forever.

New Page

A German A7V tank, deployed in 1918 in France

New Page

A German A7V tank, deployed in 1918 in France

Economic Impact

The only physical positive to come out of the war was New Zealand’s financial and trade prospects improving with European partners, making New Zealand the indispensable bread basket of Britain.

Contrasting the terrible loss of life, the battle of Passchendaele left New Zealand in a good place economically. Involvement in World War One as part of the Commonwealth saw New Zealand doing ‘their bit’ for the motherland. This tightened the bond between New Zealand and England, which meant that trade was encouraged. Therefore, New Zealand came out of the war better in some respects. The economy was protected and enhanced by the bulk-purchase trade with Britain, particularly by what was known as the ‘Protein Industry’. This trade agreement involved Britain purchasing all New Zealand produce at 25% above market price.

Furthermore, despite the shortage of labour post World War One, farmers were benefitted by the guaranteed high prices on their exports. This was a starting point of suburban New Zealand. Some returning soldiers were given uncleared land which led to new farming areas and the creation of new towns. This was a great success for these families although some men weren’t this lucky. Although infrastructure had grown during wartime, many returning troops returned from war only to find that their jobs had been filled. This ultimately caused large industrial unrest which led to the growth in popularity of the Labour party.