Hemi Maaka

Hemi Maaka

Background

A labourer from Northland, Hemi Maaka was a widower before he left for the war. His family had already suffered a great loss but the coming of war was certain to see this sorrow deepen. Heading off to war with the Maori Contingent, Maaka was posted to the Western Front on the 12th of June 1917.

The Unofficial Journal

Prevalent in the Pioneer Battalion, along with many others, this journal was a lifeblood of the Division. Containing stories, poems, and assorted articles, this smorgasbord became a centre of army correspondence and entertainment.

Off to war

'a member of the fierce and proud Pioneer Battalion'

Off to war

'a member of the fierce and proud Pioneer Battalion'

Off to War

He took part in the Battle of Passchendaele and knew firsthand the horrors of modern warfare, seeing the tragic and vain loss of life amidst the mud, rats and gas that made the Western Front resemble some form of hell. As a member of the fierce and proud Pioneer Battalion, the precursor to the Maori Battalion, Maaka served side by side with other Maori volunteers and was surely at home with the companionship of men of his own culture.

'Hurrah for the King!'

Members of the Maori contingent in the New Zealand camp at Zeitoun before their departure.

During the brutal advance of the German Kaiserschlact spring offensive in 1918, Maaka was wounded in battle and rushed from the lines. He was then transported back to England where he fought for his life against the sickness that had fell upon him as a result of his wounds. The reports sent home warned that he was, 'still dang ill'. To make matters worse, his father, Hori Maaka, had died while he was away. On August the 31st, 1919, Maaka died. He’d seen the end of the Great War but was denied the chance to live in the peace in its wake. His family had been broken by tragedy after tragedy and Hemi Maaka’s passing was surely a devastating loss.

Here lies Private Maaka

31st August 1919 – age 29.

On the wall at the Auckland War Memorial Museum

World War 1 Hall of Memories

New Page

New Page

Auckland War Memorial

Lay a Poppy for Hemi

Hemi's wounds may have taken him, yet his memory will live on forever. The amazing Online Cenotaph tool has a page specifically for Hemi, where you can leave a poppy on his tombstone to commemorate his service to New Zealand.

Imagine you are Hemi, and have just survived the Bellevue Offensive. Write us a diary entry about your experience. What was it like to fight in the freezing mud? How did it feel to see your friends from New Zealand struggling to survive? We need your voice.

Interaction

Interact

Interaction

Interact

Imagine you are Hemi Maaka, lying in a hospital bed after your father has died. Write a diary entry about your experience.

Check out the efforts of other students on our community page.

Continue your journey.

Edith McLeod

Edith McLeod

Edith was born and raised in Masterton, becoming widely loved for her kind and caring manner. Edith’s desire to help others led to her employment in Masterton hospital, where she soon became a crucial part of the local community, saving many lives and providing support to those in need. The outbreak of war in 1914 tore the Masteron region apart, as many of their young men, alongside Edith McLeod were shipped of to war, to fight or save lives.

Sent to Egypt, in 1915, Edith landed in the dusty Middle Eastern theatre of war. As the fighting raged from Egypt to Turkey, Edith served a huge amount of different troops from the Egyptian Army Hospital, from New Zealanders to Brits to Arabs.

Closer to the action in 1916, Edith arrived in Thessaloniki, Greece’s second largest city. On her way there, aboard the SS Marquette, tragedy struck. A German U Boat torpedo struck her boat, killing 32 members of the crew. Edith was one of the lucky few who survived. Her prior experience as a nurse in Masterton was hugely valuable to the war effort, which resulted in Edith's redeployment to Europe, and to the tragic battles taking place on the western front.

Edith arrived at the bloody Battle of the Somme in 1916, one of the most horrendous battles ever to occur. After surviving the horrors of the French mainland, Edith was rapidly redeployed to where New Zealand's darkest day would dawn. The muddy craters of Belgium greeted Edith in October 1917, yet this did not stop her from saving the lives of many New Zealand and Allied soldiers.

Upon the Battle's conclusion, Edith was one of the lucky few who returned home to New Zealand, where she worked in Masterton hospital for the rest of her life. Despite this, the Edith that returned, and the New Zealand she returned to, was remarkably different from 1914; the face of New Zealand had changed forever.

Life before the war

Life before the war

Life in Masterton

Edith McLeod was born and raised in Masterton before World War One. She soon became a widely loved member of the community, and many of her fellow Mastertonian's can be seen above, swimming together in the local creek.

Masterton hospital

Edith became employed in Masterton Hospital, seen above, where she worked for five years saving lives and healing those in her local community. Edith soon became one of the most well respected nurses in her area, her devotion to nursing and care for others clear to all.

The First offical NZANS nurses depart New Zealand, 1915

War declared

After the outbreak of war in 1914, local New Zealand communities were torn apart. Masterton, a town of only 5000, saw hundreds of its best men and women leave to fight a war on Britain's behalf. This left the community fearful during the war, hoping against hope that their sons, daughters, husbands, wives, mothers and fathers would return.

Edith off to the front

Not long after the outbreak of war, New Zealand responded, sending many soldiers, of the NZEF, to Turkey and later, France and Belgium. Edith, wanting to help as many as she could, managed to get herself on a boat with 50 other Kiwi's and a number of Australian nurses, bound for Egypt. Edith had no idea what she was sailing toward.

Egypt

Egypt

Egypt

As the war raged throughout Europe and the Middle East, Edith was tasked with repairing and restoring the courage of the men who had been injured fighting. She served in a number of different hospitals, from the Egyptian Army Hospital, to smaller, more less established Australian and British hospitals. Edith McLeod, a loving Masterton nurse, was thrown into the deep end, treating men with horrible wounds, both physically and mentally. She saved the lives of hundreds during her brief term in Egypt, and despite the terrible situations waiting for her each day, kept her cheery, happy manner that made her so popular in Masterton.

FROM AUSTRALIAN TENTS

With the famous pyramids in the background, Edith and her fellow Sisters saved the lives of many soldiers. The disastrous Gallipoli campaign saw many transported to Egypt with horrible injuries, which Edith treated in nothing more than a tent.

to the egyptian army hospital

The vast Egyptian Army Hospital housed huge numbers of soldiers at a time, all closely grouped together. The noise, smell and gruesome injuries would have been tremendously difficult to handle, but Edith saw the pain these men were in and felt that she had to help.

with tools like this

Without antibiotics or advanced tools, Doctors in the First World War had to rely on the most basic of equipment to save lives. Tweezers pulled bullets out of skin, scalpels cut away rotting skin and saws amputated limbs. With the bare essentials, these Doctors saved thousands of lives.

New Page

New Page

One of the many docking areas in Thessaloniki, 1915

Thessaloniki, 1915

Edith leaves egypt

As the German forces amassed on the Western Front in Europe, a number of Sisters and soldiers were transferred from the Middle East. Edith, after her frantic year in Egypt, was soon traveling toward the currently neutral Greece. Her destination, Thessaloniki, was the second largest city in Greece, yet little did Edith or her fellow passengers know what awaited her.

U boat attack

The SS Marquette, pictured above, was hit by a torpedo outside of Thessaloniki in 1915. Edith was standing under five meters away from the impact zone, where 32 members of the crew were killed. Edith, blown off her feet in the blast, did all she could to save the crew members who had been hit, yet as the boat began to sink all she could do was watch from the lifeboat as her friends, Kiwi Sisters and soldiers, drowned.

Edith, after under a week of recovery, was redeployed, her lucky escape earning her a place on the Western Front. Never one to complain, Edith did as she was asked, realising that her skill as a nurse could save the lives of many soldiers, as long as she could save her own.

New Page

New Page

Hospitals at The Somme

450,000 injured Allied forces

The Battle of the Somme saw the death of close to 150,000 Allied soldiers, the wounds inflicted on many too gruesome to recount. German machine guns mowed down thousands of soldiers who were instructed to walk into no mans land, whilst other methods of attack included poisonous gas and mine explosions.

the sisters did all they could

Into hospitals such as the one above, cold and wet, Edith and her fellow Sisters cared for men in excruciating pain. Some had inhaled chlorine gas, which burned their lungs, whilst others had numerous machine gun wounds on a single limb. In a constant, desperate struggle, Doctors amputated limbs, pulled out bullets, splinted limbs, and saved lives. Without their contribution, the Somme would be remembered as even deadlier than it turned out to be.

Equipment

tweezers and saws

The equipment available at the major battles of WW1, for Doctors and soldiers, was often terrible. Doctors were provided with tools like those above, then expected to operate on men with trench foot in icy, muddy tents. Every single life saved was done so in these conditions at these battlefield and is a true testament to the courage and skill of the medical staff.

scalpels and Syringes

Having no antibiotics, often the only course of action to take was cutting away flesh or limbs before a life was lost. With limited resources available and hundreds of desperate soldiers, Edith was pushed to her limit during the Battle of the Somme.

New Page

The Menin road in Flanders.

New Page

The Menin road in Flanders.

Two Canadian Sisters at the Battle of Passchendaele, 1917

Sisters at passchendaele

As the different conflicts that took place at Passchendaele increased in size and scale, the nurses behind the trenches were delivered men in worse and worse conditions. From the mud that covered everything, to the driving rain, to the rats running free, disease and illness ravaged the soldiers. New Zealand's darkest day dawned on the 12th of October, with close to 4000 Kiwi's falling in the following six days. This terrible number would be far greater without the tireless efforts of the medical staff, removing bullets from those still breathing and cleaning the wounds of the injured.

Without the support of these brave women, the death toll at Passchendaele would be far, far greater than it was.

New Page

New Page

Return to Masterton

Edith, after surviving the horrors of the Somme and Passchendaele, returned to New Zealand in 1918 at the war's conclusion. Yet on the boat she returned on, many were absent that had embarked for Europe in the years prior.

The impact this had on New Zealand, and especially its smaller towns, was seismic. Families were ripped apart, and many communities, such as Masterton, were left a shadow of what they were in 1914. It is painful to consider, but over a third of those young children standing on the Peace float in the left picture would be without a father or grandfather.

Edith McLeod went back to Masterton hospital, serving the rest of her life in its familiar halls, trying not to recall the terror of Passchendaele and the Somme. Her love of helping others stayed within her throughout her entire life, and her service to New Zealand in its time of need should forever be remembered with great respect and admiration.

New Page

New Page

Convince your parents you should go to war

The men need you

You are Edith McLeod. Seeing the men go off to war, your kind and caring nature urges you to help these brave soldiers with the wounds they will sustain on the battlefield. One obstacle stands in your way.

Your parents will never agree to you enrolling to be a nurse, putting your life on the line for others. The impact that you would have on the Masterton community if you stayed would be massive, and we cannot afford to lose such a superb Nurse to war.

Can you convince your loving parents that you need to be in Belgium? That you could save hundreds of lives on the battlefields in Europe and the Middle East? Or do you think that Masterton has a greater need during the war? Let us know, and write to us with your story.

Interaction

Interact

Interaction

Interact

Write a letter home from Edith McLeod at Passchendaele.

Check out the efforts of other students on our community page.

Continue your journey.

Thomas Griffiths

Thomas Griffiths

Thomas lived on Queen Street in Auckland and was educated at King’s College, he was the only son of his mother Fanny and father Thomas. In 1916, Thomas joined the Royal Naval Air Service and got his wings after he was transferred to England to learn how to fly. He was trained on a Maurice Fairman biplane at the Chingford Aerodrome in England. The Royal Naval Air Service, was not the same as the Royal Air Force or Royal Flying Corps, it was an early form of the Fleet Air Arm who experimented with ways to base planes on ships and support the Royal Navy.

Medal

After completing his training, he was assigned to fly the latest Sopwith tri-plane, and flew sorties during Bloody April.

Medal

After completing his training, he was assigned to fly the latest Sopwith tri-plane, and flew sorties during Bloody April.

Once being assigned to Number 1 naval squadron, he flew with the Aussie Ace ‘Stan Dallas,’ and in 1917 they together took on a formation of 14 Germans alone. Together the two ANZAC pilots saw off the Germans with Griffiths taking down five of their number making him New Zealand’s first Ace and meriting him to be awarded with the Distinguished Service Cross.

death

death

King and Country were quick to pin medals on heroic fighter pilots—they were the rock-stars of their day. Propaganda heavily emphasised the aces, as while their narrative boosted the nation’s morale, the tragic truth was that their stories were often cut short.

shot down

Death was a close companion of fighter pilots.

shot down

Death was a close companion of fighter pilots.

Later in 1917, he met his match against his Imperial German Navy pilot counterpart, Hans Bottler who shot him down over the skies of the Western Front. Tragically, he did not survive – in fact, pilots had a worse life expectancy than men going over the top on the ground. He never saw his mates from King’s College nor his loving family again.

Interaction

The Average life expectancy of a British Fighter Pilot during, 'Bloody April,' was only 17 and a half hours. 9 in 10 Tommies survived going, 'over the top.' Pilots had the most dangerous job of all.

Interaction

The Average life expectancy of a British Fighter Pilot during, 'Bloody April,' was only 17 and a half hours. 9 in 10 Tommies survived going, 'over the top.' Pilots had the most dangerous job of all.

After learning about the lot of an RFC pilot, would you rather gamble your life in the sky or go over the top of the trenches? Cast your ballot here and answer the call up.

Will you take your chances in the sky or head into the mud and blood of the trenches?

Write an article about Thomas Griffiths for a newspaper and try to convince more men to volunteer to fight in the war and join the Royal Flying Corps or Royal Naval Air Service.

Check out the efforts of other students on our community page.

Continue your journey.

Hugh Munce

Hugh Munce

Hugh Munce was a self employed baker in Dunedin, living with his ailing, blind father John Munce. The Munces were community men through and through, providing bread to many in their local area, and regularly attending the nearby Anglican church St Mary’s. In 1916 Hugh was conscripted to fight, and in 1917 set off on the 'Ulimaroa,' alongside his friends and fellow Dunedin-ers in the Otago Infantry Battalion. This humble baker was not a warrior, and not prepared for the horror that waited for him in Belgium.

Hugh and his fellow Kiwi’s landed in Plymouth, England and then were shipped to Dunkirk. Munce and his battalion then traveled to the Western Front arriving just after the German capture of Westhoek.

The battalion was charged with rescuing those who were injured in the attack, sent out into the allied captured Glencorse Wood.

Tragically, the German forces, just reinforced with fresh troops, began an advance into the Glencorse Wood, capturing back most of the land within it. Munce and his fellow soldiers, deep within the wood, were presumably mown down by German machine guns, yet Munce and many of his comrades, have been recorded as Missing in Action.

Life before War

Life before War

Before the War

Life in Dunedin

Hugh Munce was a self employed baker living in Dunedin with his ailing, blind father John Munce. His home, 4 Argyle Street, is shown here in all its glory.

The Dunedin Community

Dunedin bids farewell to its brave soldiers

The Dunedin Community

Dunedin bids farewell to its brave soldiers

St Mary's Anglican Church

Rebuilt in 1966

History

St Mary's Anglican Parish was established in 1883, and covered a number of districts across Dunedin, including the suburb of Mornington, where Hugh lived most of his life.

Significance

Both before, during, and after the war, the Church was a place of meeting and mourning for many of Dunedin's residents. Serving as a community hall, a place of worship, and a quiet house of reflection, the church that once sat here played a huge part in the lives of those nearby, including Hugh and his father.

Conscription

Introduced in 1916

New Zealand Needs you

The New Zealand government introduced conscription in 1916, meaning men now had to fight in the First World War. This now meant that Hugh could be conscripted at any moment, leaving his father alone.

new zealand will have you

In December of 1916, Hugh Munce was conscripted into the Otago Infantry Battalion. Hugh had never fought before in his life, his hands those of a baker, not a solider. In less than 10 months, Hugh Munce would be dead.

Off to War

Off to War

Off To War

Hugh and his fellow Dunediners in the Otago Infantry Battalion travelled to Plymouth, England in 1917 aboard the Ulimaroa.

Plymouth

The Kiwi's docked in Plymouth after a terribly long trip, only to be shipped off to Dunkirk almost immediately

Dunkirk

On the north west coast of France, Dunkirk was an important French port during World War One. The Kiwi's drew closer to the Western Front, and would be quickly sent on foot to the trenches. Many would never see Dunkirk again.

The Western Front

The Kiwi's had arrived. Blood, mud and corpses greeted these Dunedin men; Hugh could be no further from his beloved bakery and loving father than he was now.

The End

Many of these men would return

The End

Many of these men would return

The situation

A bloody battle had been waged in Polygon Wood as part of the second phase of the Battle of Passchendaele. The Glencorse Wood, a small copse of trees a few kilometers away from Polygon, saw a successful allied push, capturing the land back from the Germans. Hugh Munce and a number of his battalion, were charged with rescuing the wounded from within the Glencorse Wood.

Glencorse Wood

The New Zealand Memorial to the Missing

The Rescue

Hugh and his fellow Kiwi's traveled deep within the Glencorse Wood, searching desperately for any surviving soldiers. Yet as Hugh drew further and further into the copse, it became clear that the information he had received was incorrect. The Germans were still hiding within the trees of Glencorse Wood and the rattle of machine gun was heard too late for Hugh, nor his companions, to react.

Hugh Munce and the men that accompanied him into the Glencorse Wood, have never been found.

New Page

Kiwi's waited anxiously for their children to return.

Hugh's father would never see his son again

New Page

Kiwi's waited anxiously for their children to return.

Hugh's father would never see his son again

We Will Remember Them

Hugh and his fellow Kiwi's who fell in the Belgian mud, may have never been found but, their sacrifice will not be forgotten. Preserving the lives of these men in New Zealand's history will take time and effort, but this is a small repayment for their ultimate sacrifice.

What can you do? Find an Anzac on our website, and learn who they were, where they lived, and what they gave for their country. Next, put yourself in the shoes of Hugh, Edith, Otto, or any other brave Anzac. Write to us with your stories. Lay a poppy for these brave men and women, learn about their hometowns, their families, and their communities. But don't stop there. Thousands of Anzac stories have been lost, stories that should not be forgotten.

Only in forgetting these men and women will their sacrifice be truly lost.

New Page

New Page

Will you be sent off to war?

A conscription box identical to this would have sealed the fate of Hugh Munce

Conscription boxes such as this one were used to select the Kiwi's who would be shipped off to war. The chances of being selected were scarily high, as was the chance of dying during the war if you were one of the unlucky few, such as Hugh, who were drawn out of a box such as this. The name of every able bodied man in your region, excluding Maori, was put into a box like the one above. The box was cranked about, and then the names would be removed and read out to the nervous reporter.

Your chance of being sent off to war is the same as rolling a 5 on two die. Use the interactive tool below to see whether you would be conscripted, then write us a letter from the front. What is life like in the trenches? Did you see Hugh make his final walk into the Glencorse woods? Tell us your stories, share them on our social media sites. We shall never forget.

Interaction

Lest We Forget

Interaction

Lest We Forget

Imagine you are Hugh Munce. Describe how you would have felt learning that you have been conscripted.

Check out the efforts of other students on our community page.

Cunliffe's Video

Cunliffe's Video

Rifleman Roy Cunliffe

This is the story of Rifleman Roy Lane Cunliffe from Wellington, watch the video—originally made for our Facebook page—to learn more about this soldier’s story.

New Page

Cunliffe’s story is not over…

New Page

Cunliffe’s story is not over…

Above is Roy’s cross for the Field of Remembrance that was placed outside the War Memorial Museum as part of the centenary of the Armistice at the end of the Great War. We are currently in possession of it and if you are a descendant of Cunliffe, and you can prove that he is your ancestor, we’d be very happy to pass it on to you. Please, if you are indeed related to this fallen soldier of the Great War, get in touch using the form below.

Tamati

It’s a Dirty Job…

Tamati

It’s a Dirty Job…

…But Someone’s Got to Do it: A Pioneer's story:

Private Tamati Te Patu MM volunteered for service in 1915, he was a farmer from Karioi and ended up doing a job quite unique to the Great War. Tamati was a pioneer. As part of New Zealand’s Pioneer battalion—an engineering unit—-tasked with digging trenches and creating fortifications —Tamati was sent to Messines after his training in Suez.

When the village of Messines was captured, it needed to be linked and incorporated into the new front line, a job simple to do on a map but much harder in reality. Tamati's task was to literally redraw the lines of the battle, by digging the trenches connecting the new British front line to the newly captured territory. Whilst not a desirable task, it was not combat duty and Tamati would not have expected the following events which allow me to write the, 'MM,' after his name.

The Military Medal

"On the 7th June Pte Te Patu was on a working party who were digging a communication trench to the German 2nd Line. The party came under very heavy shellfire and Te Patu was wounded in the neck, shoulder and arm. Though he was bleeding profusely and was told that he might go back to the dressing station, he declined to do so and insisted that he must finish his work so his comrades should not have to remain behind and complete it for him. He thus set a very fine example of pluck and devotion to duty, which was of the greatest value at such a trying time."

As the official citation goes, Tamati Te Patu's conduct was exemplary and a fascinating example of how bravery and heroics in battle don't have to be achieved with the killing of the enemy, but the commitment to duty required to save one's friends. The Military Medal is one of the highest honours British Servicemen or women can be awarded, it is just short of the Distinguished Conduct Medal and the Victoria Cross (VC). The honour is such that the bearer of the medal may write the initials MM after their name.

After the Great War…

Tamati went on to serve during the Second World War as a Sergeant. He was tasked with guarding Japanese POWs. After the Second World War, Tamati continued to work alongside the military in a motor and electrical engineering capacity. At the age of 65, he retired. Tamati was awarded a number of medals for long service and good conduct during his military career. On the 10th of January 1984, Tamati passed away nearby the camp at Trentham, where he first signed up to join the fight in two World Wars.

Rupert

What happened to him?

Rupert

What happened to him?

Without a Trace:

This is the story of a young soldier who disappeared in Flanders. All that remains of him is his photograph, a letter he sent his mother and an embroidered gift. Find out what happened and lay a virtual poppy for this lost soldier of the Great War.

Rupert Sydney Taucher was born in 1895, in Carterton in the North Island of New Zealand. Taucher enlisted in the Territorials in the 16th Waikato Regiment and completed two years of service. When the war began, he was working as a labourer in Te Kuiti.

What do you think happened to Private Taucher? Lay a poppy for him on his online cenotaph page here: http://www.aucklandmuseum.com/…/online-cenota…/record/C15478

The gift and postcard Rupert sent his family, all that remains of him.

To war:

In September of 1916, he became 33476 Private Rupert Taucher of the Wellington Infantry Regiment and set sail for England and the Great War aboard the troopship, Ulimaroa. After training on the Salisbury plain he was sent to France.

Rupert was attached to the 17th Ruahine Company and survived a gunshot wound in France. After his convalescence, it was time for Taucher to return to the lines; this time Flanders. Rupert was posted to Ieper (Ypres) near Passchendaele.

Flanders:

During his time in Flanders, Taucher was sent out on a cable laying missions with his unit. On one such mission on the 24th of November 1917, Taucher vanished. The rest of his unit reported in after the mission was finished--without Rupert. What happened to Private Taucher remains a mystery. An official inquiry saw witnesses testifying to his presence in the party, appearing well and able. The ruling was that Taucher was, “Reasonable to suppose dead in the field on 24 November 1917."

Taucher's body was never found. He is commemorated in the New Zealand grounds of Buttes New British Cemetery, at Polygon Wood in Zonnebeke.

The Mud Sea:

One possible explanation is that he fell into a flooded shell crater and drowned in the mud.

Australians at Passchendaele

Australians at Passchendaele

The Australians at Passchendaele:

While our site mainly focuses on the service and sacrifice of New Zealanders at Passchendaele and on the wider Western Front, it is important to remember the contributions of our Commonwealth cousins and fellow ANZACs. Australian soldiers also participated in the Battle of Passchendaele. This article follows the story of the men of the 8th Battalion and was inspired by a remarkable photograph of some of its members at Passchendaele. This story serves as an example for our site of the service of Australian soldiers during the Great War.

The 8th Battalion:

Among the Australians who fought at Passchendale were the men of 8th Battalion, Australian Imperial Force. This unit was comprised primarily of rural Victorians and raised from volunteers in 1914. Like many other Australian units, the 8th suffered heavy casualties over the course of the war, but it initially started with a strength of around 1000 men.

The Badge of the 8th Battalion

Worn on its soldiers’ uniforms

As they were formed so early in the war, the 8th Battalion fought in most of the major battles that the ANZAC forces were committed too. Pictured below, you can see men of C Company, 8th Battalion visiting the pyramids before they would face their baptism of fire at Gallipoli. The 8th Battalion landed at Anzac Cove and fought at Cape Helles and Lone Pine before being evacuated from the Gallipoli Peninsula.

Pozières

Soldiers of the 8th…

…Watching No Man’s around Pozières

After seeing action at Gallipoli, the 8th was sent back to Egypt before finally departing for the Western Front and the rest of their war. Upon arriving in France, the 8th’s first major action was part of a major Australian offensive during the Battle of the Somme. The 8th were sent with the Australian divisions to Pozières. The goal of the Australian attack was to take a ridge from where a later attack might be staged to capture the strategic position of Theipval. The Australian attack was split between the troops sent to take the village of Pozières and those sent to occupy the higher ground. The village was successfully captured and held on the 29th of July, the assault on the heights began at 12:15am on the 29th of July 1916. The Germans were better prepared in this location and the assault failed at the cost of 3,000 Australian casualties. It was only after the use of heavy artillery bombardment that the heights fell to the Aussies on the 4th of August. The action at Pozières cost the Australians 23,000 casualties with 6,800 dead. The 8th Australian Battalion had suffered 300 casualties at the Somme.

Pte Thomas Cooke

Thomas Cooke while he was an acting Corporal

One of the 8th Battalion’s soldiers stationed at the Somme, was New Zealand-born Pte Thomas Cooke. Cooke came from Kaikoura and won a posthumous Victoria Cross for his last stand at Pozières. Cooke was the final soldier of his team to be killed as he defended the line with his Lewis machinegun on the 25th of July 1916.

Aussies Western Front

Onward down the Menin Road

Aussies Western Front

Onward down the Menin Road

Into Flanders:

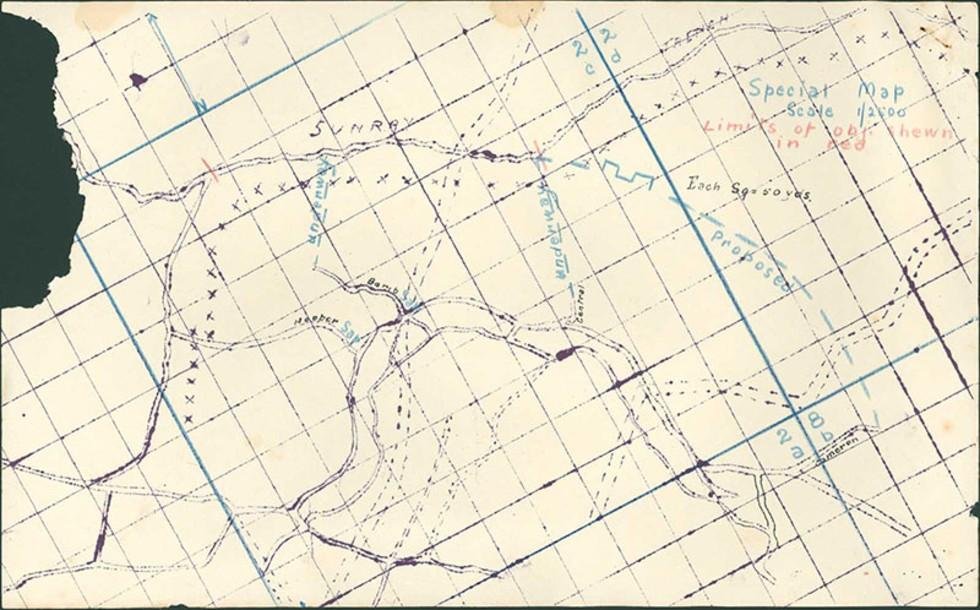

The 8th, having survived Pozières, were rested before marching down the Menin Road. Orders for one of their planned attacks (see below) reveal the detailed tactical preparations underpinning some First World War actions. This suggests that despite what many may now believe, not all offensives during the Great War were poorly planned and suicidal. The orders for the attack came as a result of news that the Germans had abandoned many of their positions – retreating to the heavily defended Hindenburg Line (the events of the German retreat to this line are covered in the film 1917). A survivor of one of the attacks on the Menin Road in September 1917, Pte George Radnell, (8th Battalion) recorded the following details:

“Hogg pushed up to a pillbox in Glencorse Wood. Collected some fine souvenirs there ... gas in one pillbox. Two wounded Fritzs in one and helped them to the dressing station.”

Australian Orders for an Attack on the Menin Road:

The Australians followed the Menin Road to their next destination; the 8th was bound for Passchendaele.

Passchendaele

The 8th then went on to participate in the Battle of Passchendaele. The toll that this event took on the men of the 8th can be seen in their faces in the following photographs. Below the colourised photo, each soldier who could be identified is named and numbered, some of their stories are told below.

Men of the 8th Battalion, 28th October 1917 – Passchendaele

Identified are: 442 Sergeant (Sgt) Robert Alexander McLean from Beeac, Victoria (1); unidentified (2); 1639 Sgt Percy Gye Flemington, Victoria (3); 1423 Private (Pte) Henry John Streets from Portsmouth, UK (4); 4444 Pte Thomas Alexander Brown from Golden Square, Victoria (5); 5208 Pte Eric Clinton Teague from Bendigo, Victoria (6); 3800 Sgt Arthur Ronald Holloway from Chiltern, Victoria (7); 4615 Pte Matthew Trewhella from Bendigo (8); unidentified (9); unidentified (10); 131 Pte E M Hughes, Royal Garrison Artillery (RGA) (11); unidentified (12); 5088 Pte H J Floate, RGA (13); unidentified (14); unidentified (15); unidentified (16); 5246 Lance Corporal (L Cpl) James Callil Ferry from Carlton, Victoria (17); unidentified (18); L Cpl Benjamin Crosby from Richmond, Victoria [killed in action in Belgium 8 July 1916] (19); 2936 Corporal (Sgt) John Thomas Pinchen MM from South Melbourne, Victoria (20); 5454 Pte David Styles from Hamilton, Victoria (21); 7150 L Cpl Harold James Gray from Parkville, Victoria (22); 3115 Sgt Bernard Gordon Murphy from West Melbourne (23); 5107 Pte Herbert Edward Hellyer from Cavendish, Victoria (24); unidentified (25); 6728 L Cpl Reginald Miller Cullen from Temora, NSW (26); Lieutenant John Gibson Pitt from Surrey, UK (27); 5443 L Cpl Samuel Redmayne from Alexandra, Victoria (28); Captain Alexander George Campbell DSO from Sandringham, Victoria (29); 3831 Sgt Leslie Gordon Kittle MM from Shepparton, Victoria (30); 2017 Pte David Owen MM from North Melbourne (31); 1111 Sgt Jack John Jorgenson from Hawthorn, Victoria (32); 2423 Pte Arthur Leslie Beachcroft from Moonee Ponds, Victoria (33); Pte Trevalla (34); 354 Sgt Allan Couper Robertson from Leongatha, Victoria (35); unidentified (36); 1839 Pte William John Thomas from Geelong, Victoria (37); 2448 Pte Albert James Radley from Dunkeld, Victoria (38); 4306 Pte Blain Stanley Skinner from Albert Park, Victoria (59).

Stories:

Captain Alexander George Campbell (DSO)

Number 29, Alexander George Campbell (DSO), can be seen literally leaning for support on his NCOs – powerful symbolism for the roles of both officers and men. No doubt, Alexander is exhausted as this photo was taken after the men were withdrawing from the front line. The Captain was awarded a Distinguished Service Order and was wounded severely three times over the course of the war and died in a plane crash in 1936.

Sergeant John Thomas Pinchen MM

Number 20, John Thomas Pinchen MM, was twice completely buried by shell firing. He won a Military Medal for gallantry at Zonnebeke. The citation (below) for Pinchen’s medal describes his inspiring presence on the firing line and the impressive leadership he showed as a Non-Commissioned Officer.

Sergeant Allan Coupar Robertson

The file describing Allan’s wounds at Gallipoli

Number 35, Allan Coupar Robertson, known as ‘Robbie’ to his men is pictured with a distinctive scar on his face. This is because Allan was shot in the face at Gallipoli and even suffered another gunshot wound in 1916. Allan’s files also reveal that he was promoted and demoted on occasion throughout the course of the war. It seems that he was initially a bit of a troublemaker, arguing with his officers and enjoying the company of some of the local women. However, Allan regained his rank of Sergeant to full establishment and led the 16th platoon in defence of a position near Nieppe forest. Robertson was well regarded by his men who remembered him for his height (5’9, tall at the time) and strong build according to enquiries made about him by the Red Cross.

How Allan’s story ended…

Robertson was killed on the 27th of April 1918, either by a German minenwerfer blast or a machine gun, according to the reports of some of his men. Robertson’s father and brother were also killed during the Great War.

The oath that Allan – along with all other British and Empire soldiers – signed; swearing to do his duty for King and Country…

By the end of the Great War, the 8th battalion had suffered around 3,000 casualties (300% casualty rate), meaning the strength of the unit after it had been reinforced several times, was effectively killed or wounded three times over. During 1917, more than 75,000 Australians were either killed or wounded on the Western Front.

While our focus is on New Zealanders’ service, this story is shared in recognition of our companionship as members of the Commonwealth (after all, this Australian themed article was completed by an Englishman living in New Zealand, with additional research by a Canadian!) – a testament to our cooperation and shared history.

Banner Below:Identified, sitting at left, back row: Lieutenant (Lt) J O Pitt; Captain A G Campbell DSO. Front row: Lt T W Johnstone MC; Second Lieutenant P Lay MC DCM MM. Standing, left to right: 7150 Lance Corporal (LCpl) H J Gray, resting on shovel (killed in action 17 December 1917); 2936 Sergeant (Sgt) J T Pinchen MM; 2778 LCpl L A Scouller MM, behind Pinchen (killed in action 26 August 1918); 1111 Sgt J R Jorgenson; 6728 Pte R M Cullen. The soldier whose head can be seen top left is unidentified.

The Rhind Brothers

The Rhind Brothers

WORK IN PROGRESS:

This personal story is currently in the works and will follow the lives and deaths of the Rhind Brothers from Lyttleton, who fought in the Great War in many of New Zealand’s most pivotal battles. Check out some of our other stories in the meantime and check back later for this exciting story, it will be our most ambitious yet.

Otto Schmidt

Otto Schmidt

As it was for many Germans, the declaration of war was a dream come true. A former hunter from Bavaria, Otto had been down on his luck, and had moved to the city to find work. The declaration of the war meant that Otto could join the army for a bellyful of food and a steady wage. He volunteered at the start of the war and was sent to the Western Front. By the time of the British attack at Passchendaele, Otto was a sergeant in the German 4th Army. Otto had become hardened by his experiences and by the loss of so many of the young men who had come to rely on him as their commander.

Patriotism, a love of the Fatherland and the promise of fair pay and warm food had drawn so many into the blut und stahl, blood and steel of the Western Front. Otto had been defending the salient at Bellevue before the ANZACs advance. After the opening bombardment ceased, Otto was sure to have expected an imminent attack, and unfortunately for him, it came. The guns opened up on the advancing British troops but due to the artillery many of the machine guns and their operators were out of action and the advance couldn’t be stemmed. While Otto tried to organise his men, he surely didn’t hear the clattering of the mills bomb as it bounced into the trench floor over the noise of the battle ... nor would he have heard the subsequent explosion that killed him.

New Page

'Patriotism, a love of the Fatherland and the promise of fair pay and warm food had drawn so many into the blut und stahl – the blood and steel of the Western Front.'

New Page

'Patriotism, a love of the Fatherland and the promise of fair pay and warm food had drawn so many into the blut und stahl – the blood and steel of the Western Front.'

Otto would have been familiar with the German tactic of conceding territory to the enemy and then counterattacking and gaining it back. However, at Bellevue Spur, the Germans did not need to feint the ANZACs and bait them into a trap as they had the New Zealanders pinned down before their formidable defences. There was no hope for the attacking New Zealanders to capture the German positions as the barbed wire between them and the German trenches remained uncut.

While Otto fell in defence of Bellevue Spur, a great many more New Zealanders died that day and those who were wounded lay out in No Man’s Land, all night. It must have been horrifying for the Germans to hear the many wounded New Zealanders left out that night and even worse for the wounded ANZACs who had to wait for a truce to be rescued. However, despite the attack on Bellevue Spur being New Zealand’s Darkest Day, when the light broke through the clouds the next morning, the Germans agreed to let New Zealand stretcher bearers retrieve the wounded, the dying and the dead.

New Page

New Page

Would You hear the Grenade?

Mills Bomb

The deadly grenades of the First World War

can you hear that?

The Mills bomb was a popular hand grenade used by the British in World War One. It was often lobbed into a trench, or hurled at a tank, in order to slow down or kill the enemy. These hand grenades proved to be very deadly in the right hands and occasionally, soldiers wold carry a great many into battle against the often well defended German positions.

Otto, taking desperate pot shots at the enemy as they advanced toward him and his men, shouting orders to his men, would have not heard the small Mills bomb that bounced onto the trench floor next to him and exploded. The sound of the Great War is not something easily reproduced or experienced today, but it would have been deafening—especially considering that most soldiers possessed no form of hearing protection. Would you hear the small hand grenade tumbling around on the ground? Play the track below to get a small sense of how chaotic the battlefields of the Western Front must have been.

Interaction

Interact

Interaction

Interact

Compare and contrast a German soldier’s experiences of the Great War with that of a New Zealand or British Empire soldier’s. What motivated them to fight? How were they similar? How were they different?

Check out the efforts of other students on our community page.

Continue your journey.